Xiongnu language

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2024) |

| Xiongnu | |

|---|---|

| Xiong-nu, Hsiung-nu | |

| Native to | Xiongnu Empire |

| Region | eastern Eurasian Steppe |

| Ethnicity | Xiongnu |

| Era | 3rd century BCE-1st century CE?[a] |

| Dialects | |

| recorded with Chinese characters | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

| Glottolog | xion1234 |

Map of the Xiongnu Empire, where the Xiongnu language was spoken. | |

Xiongnu, also referred to as Xiong-nu or Hsiung-nu, is the language(s) presumed to be spoken by the Xiongnu, a people and confederation which existed from the 3rd century BCE to 100 AD. It is sparsely attested, and the extant material available on it comprises about 150 words, as well as what may be a two-line text transcribed using Chinese characters,[6] which the Xiongnu may have used themselves for writing their language.[7]

Attestation

[edit]Apart from tribal and sovereign names, some words, a song in the potentially related Jie language, and Chinese descriptions, the language(s) of the Xiongnu is very poorly documented, and very fragmentarily attested.

Classification

[edit]The origin of the Xiongnu is disputed and no theory has more support than another.

Xiongnu, with our current information, is unclassifiable[8] or a language isolate,[9] that is, a language whose relationship with another language is not apparent.

Turkic language

[edit]According to Savelyev and Jeong (2020):[10]

The predominant part of the Xiongnu population is likely to have spoken Turkic.

However, on the basis of genetics, the Xiongnu were likely multiethnic.[10]

Wink (2002) suggests that the Xiongnu spoke an ancient form of Turkic, and if they were not Turkic themselves, that they were influenced by Turkic peoples.

Benjamin (2007) proposes that the Xiongnu were either Proto-Turks or Proto-Mongols, and that their language would have been similar to that of the Dingling.

Chinese historical works link the Xiongnu to various Turkic peoples:

- The ruling dynasty of the Göktürks were originally part of the Xiongnu.

- The Uyghur khagans claimed Xiongnu ancestry.

- The Book of Wei states that the Yueban were descended from the northern Xiongnu. It is also stated that Yueban language and customs were similar to those of the Tiele.

- The Book of Jin lists 14 southern Xiongnu tribes who entered Old Yan[specify], and some of the tribal names have been compared to Old Turkic.

(Para-)Yeniseian language

[edit]In the 20th century, Lajos Ligeti was the first linguist to hypothesize on the Yeniseian origin of the Xiongnu language. In the early 1960s, Edwin Pulleyblank further developed this theory and added evidence.

The Yeniseian origin theory proposes that the Jie, a Western Xiongnu people, were Yeniseians.[11] Hyun Jin Kim found similarities in a Jie-language song in the Book of Jin (composed during the 7th century) to Yeniseian.[12][13][failed verification] Pulleyblank and Vovin then affirmed that the Jie were the minority ruling class of the Xiongnu, ruling over the other Turkic and Iranian groups.

According to Kim, the dominant language of the Xiongnu was likely Turkic or Yeniseian, but their empire was multiethnic.

It is possible that Xiongnu nobility titles originated from Yeniseian and were loaned into Turkic and Serbi-Mongolic languages:[9][14]

- The words "tarqan", "tegin", and "kaghan" originate from Xiongnu, and they may therefore have a Yeniseian origin.

- The Xiongnu word for "heaven" may be derived from Proto-Yeniseian *tɨŋVr.

Certain Xiongnu words appear to be cognate with Yeniseian:[14][15]

- Xiongnu kʷala "son" compared to Ket qalek "younger son".

- Xiongnu sakdak "boot" compared to Ket sagdi "boot".

- Xiongnu gʷawa "prince" compared to Ket gij "prince".

- Xiongnu dar "north" compared to Yugh tɨr "north"

- Xiongnu dijʔ-ga "clarified butter" compared to Ket tik "clear"

According to Pulleyblank, the consonant cluster /rl/ appears word-initially in certain Xiongnu words. This indicates that Xiongnu may not have a Turkic origin. Most of the attested vocabulary also appears Yeniseian in nature.[16]

Vovin remarks that certain horse names in Xiongnu appear to be Turkic with Yeniseian prefixes.[14]

Savelyev and Jeong doubt the theory of Yeniseian origin as the Xiongnu genetically correspond to Iranians, unlike Yeniseians, who have a strong Samoyedic affinity.[10]

It is also possible that Xiongnu is linked to Yeniseian in a Para-Yeniseian phylum, both linked in a Xiongnu-Yeniseian family, but others believe it was a Southern Yeniseian language.[15][17]

As a result, there are two competing models for the classification of Xiongnu into Yeniseian:

Yeniseian model

[edit]- Northern Yeniseian

- Southern Yeniseian

- Assanic

- Pumpokolic

- Xiongnu

Para-Yeniseian model

[edit](Para-)Mongolic language

[edit]Certain linguists posit that the Xiongnu spoke a language similar to Mongolic. According to some Mongolian archaeologists, the people of the slab-grave culture were the ancestors of the Xiongnu, and some scholars believe the Xiongnu were the ancestors of Mongols.

According to Bichurin, the Xianbei and the Xiongnu were the same people, just with different states.[18]

The Book of Wei indicates that the Rouanrouans were descendants of the Donghu. The Book of Liang adds:

They [the Rouanrouans] also constituted a branch of the Xiongnu.

Ancient Chinese sources also designate various nomadic peoples to be the ancestors of the Xiongnu:

- The Kumo Xi, speakers of a Para-Mongolic language

- The Göktürks, who spoke the Orkhon Turkic language (or Göktürk), a Siberian Turkic language.

- The Tiele, who also spoke Turkic.

Other elements seem to indicate a Mongolic or Serbi-Mongolic origin of the Xiongnu:

- Genghis Khan designated the era of Modu Chanyu, in a letter addressed to the Taoist Qiu Chuji, as "the bygone times of our Chanyu".

- Xiongnu solar and lunar symbols resemble the Mongolic Soyombo symbol.[19]

Iranian language

[edit]On the basis of Xiongnu names of nobility, it was proposed that the Xiongnu spoke an Iranian language.

Beckwith suggests that the name "Xiongnu" is cognate with the word "Scythian", or "Saka", or "Sogdian" (all referring to Central Iranian peoples).[20][21] According to him, the Iranians directed the Xiongnu and influenced their culture and models. [20]

Harmatta (1994) affirms that Xiongnu names are of Scythian origin, and that Xiongnu would therefore be an Eastern Iranian language.

According to Savelyev et Jeong (2020), ancient Iranians contributed significantly to Xiongnu culture. Additionally, genetic studues indicate that 5% to 25% of Xiongnu were of Iranian origin.[10]

Other possible origins

[edit]Other, less developed, hypotheses posit that Xiongnu is of Finno-Ugric[22] or Sino-Tibetan affiliation.[23] It is possible that some eastern Xiongnu peoples may have spoken a Koreanic language.[24][25][26][27]

Multiple languages

[edit]A more developed and supported hypothesis than the previous ones indicate a multiethnic origin, and the primary language of the Xiongnu would be too poorly attested to conclude a relationship to any other language.[28]

Possible link with Hunnic

[edit]

Some researchers suggest a linguistic connection between the Huns, Hunas, and the Xiongnu people,[29] However, this is debated, as there is also the possibility that the Huns, despite sharing the same migration route and having relations with the Xiongnu, originated from Indo-European peoples.[30] In 2005, As-Shahbazi suggested that there were originally a Hunnish people who had mixed with Iranian tribes in Transoxiana and Bactria, where they adopted the Kushan-Bactrian language.[31] It should be known that there is no consensus about the linguistic origins of the Huns. Some scholars have suggested that the Huns originated from Mongolic or Turkic groups, making them possibly linguistically distinct from the Xiongnu people.[32][33]

Contact with Chinese

[edit]

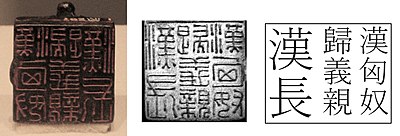

The Xiongnu had mutual contact with the Chinese civilization, and the Chinese were their sole contact with the outside world besides the tribes around them which they were the dominating force above them.[35] In 53 BC, Huhanye (呼韓邪) decided to enter into tributary relations with Han China.[36] The original terms insisted on by the Han court were that, first, the Chanyu or his representatives should come to the capital to pay homage; secondly, the Chanyu should send a hostage prince; and thirdly, the Chanyu should present tribute to the Han emperor. The political status of the Xiongnu in the Chinese world order was reduced from that of a "brotherly state" to that of an "outer vassal" (外臣). One of the most significant inscriptions in the Xiongnu language, found in the Xiongnu capital Longcheng, was written in Chinese characters and spell out *darƣʷa, meaning "leader" or "chief".[37] There also were a Xiongnu inscription unearthed in Buryatia that has Chinese characters written on it, suggesting that Chinese alphabet was in usage in the area of this is result of Han influence via trade networks.[38] Another inscription that uses Chinese characters is located in the loyal tomb complex of the Xiongnu that spells out:

[乘輿][...] [...] [...]年考工工賞造 嗇夫臣康掾臣安主右丞臣 [...] [...]令臣[...]護工卒史臣尊省, It translates: [Fit for use by the emperor] made in the [?] year of the [? era] by the master artisan of the Kaogong imperial workshop Shang. Managed by the workshop overseer, your servant Kang; the lacquer bureau head, your servant An. Inspected by the Assistant Director of the Right, your servant [?]; the Director, your servant [?]; and the Commandery Clerk for Workshop Inspection, your servant Zun.[39]

Xiongnu influence in the Chinese language includes the Chinese word for lipstick (胭脂) which spells out as *'jentsye and derives from the Xiongnu word for wife (閼氏) which is spelled out in the same manner.[40] Several terms in animal husbandry, including names for different species of horses and camels that have uncertain foreign-originating etymologies, also had been suggested to have Xiongnu origins.[41] The name of the Qilian Mountains also originates from Xiongnu. A Xiongnu deity named Jinglu (徑路) was depicted as a sword and the spelling is the same as the Chinese word for "path" or "way". This deity had a temple dedicated to him and the worship included carving gold using the holy knife.[42][43][4]

After the dissolution of the Xiongnu, a few tribes remained to exist, which were the tribes of Chuge, Tiefu, Lushuihu, and Yueban. Except for the Yueban, also called the Weak Xiongnu, the rest of the tribes migrated to China and started their own settlements. One of those unique settlements is Tongwancheng, which has a mixed Xiongnu and Chinese etymology, specifically 統萬 (tongwan), a possible cognate with the word tümen which exists in both Turkic and Mongolian, meaning "leading 10,000" or "leading a myriad".[4]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bacot J. "Reconnaissance en Haute Asie Seplentrionale par cinq envoyes ouigours au VIII siecle" // JA, Vol. 254, No 2,. 1956, p.147, in Gumilev L.N., "Ancient Türks", Moscow, 'Science', 1967, Ch.27 http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/OT/ot27.htm (In Russian)

- ^ Tishin, V.V (2018). ["Kimäk and Chù-mù-kūn (处木昆): Notes on an Identification" https://doi.org/10.17746/1563-0110.2018.46.3.107-113]. p. 108-109

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ a b c Chen, Sanping (1998). "Sino-Tokharico-Altaica — Two Linguistic Notes". Central Asiatic Journal. 42 (1): 24–43. JSTOR 41928134.

- ^ Xiong, Victor (2017). Historical Dictionary of Medieval China. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 315. ISBN 9781442276161.

- ^ Vovin 2000, p. 87.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander (2020). "Two Newly Found Xiōng-nú Inscriptions and Their Significance for the Early Linguistic History of Central Asia". International Journal of Eurasian Linguistics. 2 (2): 315–322. doi:10.1163/25898833-12340036. ISSN 2589-8825.

- ^ "Glottolog 4.6 - Xiong-Nu". glottolog.org. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- ^ a b Di Cosmo 2004, p. 164.

- ^ a b c d Savelyev & Jeong 2020.

- ^ Vovin, Edward Vajda & Étienne de la Vaissière 2016.

- ^ Hyun Jin Kim 2013.

- ^ Hyun Jin Kim 2015.

- ^ a b c Vovin 2003.

- ^ a b Vovin 2015.

- ^ Pulleyblank, Edwin George (1963). "The consonantal system of Old Chinese. Part II" (PDF). Asia Major. 9: 264. Retrieved 2011-02-06.

- ^ Vovin 2000, p. 87-104.

- ^ N. Bichurin 1950.

- ^ Miller, Bryan (2009). "Elite Xiongnu Burials at the Periphery: Tomb Complexes at Takhiltyn Khotgor, Mongolian Altai (Miller et al. 2009)". Academia. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- ^ a b Beckwith 2009, p. 71-73.

- ^ Beckwith 2009, p. 405.

- ^ Di Cosmo 2004, p. 166.

- ^ Jingyi Gao 高晶一 (2017). "Xia and Ket Identified by Sinitic and Yeniseian Shared Etymologies // 確定夏國及凱特人的語言為屬於漢語族和葉尼塞語系共同詞源". Central Asiatic Journal. 60 (1–2): 51–58. doi:10.13173/centasiaj.60.1-2.0051. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ "騎馬흉노국가 新羅 연구趙甲濟(月刊朝鮮 편집장)의 심층취재". monthly.chosun.com (in Korean). 2004-03-05. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ 교수, 김운회 동양대 (2005-08-30). "금관의 나라, 신라". www.pressian.com (in Korean). Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ 조선일보 (2020-08-04). "경주 사천왕사(寺) 사천왕상(四天王像) 왜 4개가 아니라 3개일까". 조선일보 (in Korean). Archived from the original on December 30, 2014. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ "자료검색>상세_기사 | 국립중앙도서관" (in Korean). 2018-10-02. Archived from the original on 2018-10-02. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Di Cosmo 2004, p. 165.

- ^ Vaissière, Étienne. "Xiongnu". Encyclopedia Iranica..

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen, Otto J. (1944–1945). "Huns and Hsiung-Nu". Byzantion, Vol. 17: 222–243..

- ^ Shapur Shahbazi, A. "SASANIAN DYNASTY". Encyclopædia Iranica Online Edition. Retrieved 2012-09-03.

- ^ Parker, Edward Harper (1896). "The Origin of the Turks". The English Historical Review. 11 (43): 431–445. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 547136.

- ^ Taşağıl, Ahmet (1 May 2005). "TURKISH - MONGOLIAN RELATIONS IN THE EARLY PERIOD". Manas Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi. 7 (13): 20–24. ISSN 1694-5093.

- ^ Psarras, Sophia-Karin (2 February 2015). Han Material Culture: An Archaeological Analysis and Vessel Typology. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-316-27267-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kim, Hyun Jin (29 March 2017). "The Xiongnu". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.50. ISBN 978-0-19-027772-7.

- ^ Grousset 1970, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander (1 December 2020). "Two Newly Found Xiōng-nú Inscriptions and Their Significance for the Early Linguistic History of Central Asia". International Journal of Eurasian Linguistics. 2 (2): 315–322. doi:10.1163/25898833-12340036.

- ^ Otani, Ikue (1 July 2020). "A reconsideration of a Chinese inscription carved on lacquerware unearthed from Barrow No. 7 of the Tsaram Xiongnu cemetery (Buryatia, Russia): new reflections on the organization of the central workshops of the Han". Asian Archaeology. 3 (1–2): 59–70. doi:10.1007/s41826-019-00025-y.

- ^ Miniaev, Sergey. "Investigation of a Xiongnu Royal Tomb Complex in the Tsaraam Valley".

- ^ Zhingwei, Feng. "发表于《Aspects of Foreign Words/Loanwords in the Word's language》 (The Multi-Faceted Nature of Language Policies that Aim to Standardize and Revive Language), Proceedings for 11th International Symposium, The National Institute for Japanese Language, p200-229, 2004, Tokyo" (PDF).

- ^ Şengül, Fatih (1 January 2020). "The Horse-Related Terms and Animal Names in the Language of Xiongnus (Asian Huns)".

- ^ Schuessler, Axel. "Phonological Notes on Hàn Period Transcriptions of Foreign Names and Words" in Studies in Chinese and Sino-Tibetan Linguistics 53.

- ^ Miller, Bryan K. (2024). Xiongnu: The World's First Nomadic Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-008369-4.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ts. Baasansuren (Summer 2010). "The Scholar Who Showed the True Mongolia to the World". Mongolica. 6 (14). pp. 40

- Harold W. Bailey (1985). Indo-Scythian Studies: being Khotanese Texts. Cambridge University Press. JSTOR 312539. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (16 March 2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- Craig Benjamin (18 April 2013). The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-06722-6. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- N. Bichurin (1950). Collection of information on the peoples who inhabited Central Asia in ancient times.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola (2004). Ancient China and its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- Shimin Geng (2005). 阿尔泰共同语、匈奴语探讨 (in Chinese). 语言与翻译. ISSN 1001-0823. OCLC 123501525. Archived from the original on 2012-02-25. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- Peter B. Golden (1992). "Chapter VI – The Uyğur Qağante (742–840)".". An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East. Wiesbaden: O. Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-03274-2. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- Peter B. Golden (2013). Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran. Iași: Curta, Maleon.

- Peter B. Golden (August 2018). The Ethnogonic Tales of the Türks. The Medieval History Journal. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- János Harmatta (1 January 1994). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 B. C. to A. D. 250. UNESCO. ISBN 978-9231028465. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- Andreas Hölzl (2018). A typology of questions in Northeast Asia and beyond. Martin Haspelmath. p. 532. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1344467. ISBN 978-3-96110-102-3. ISSN 2363-5568. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- Huang Yungzhi; Li Hui (2017). The genetic and linguistic evidence for the Xiongnu-Yenisseian hypothesis (PDF). Man in India. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- Hyun Jin Kim (2013). The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00906-6.

- Hyun Jin Kim (November 2015). The Huns. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1317340904. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- Joo-Yup Lee (2016). The Historical Meaning of the Term Turk and the Nature of the Turkic Identity of the Chinggisid and Timurid Elites in Post-Mongol Central Asia. Central Asiatic Journal.

- Savelyev, Alexander; Jeong, Choongwoon (7 May 2020). "Early nomads of the Eastern Steppe and their tentative connections in the West". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 2. doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.18. hdl:21.11116/0000-0007-772B-4. PMC 7612788. PMID 35663512.

- Denis Sinor. Aspects of Altaic Civilization III.

- D. Tumen (February 2011). Anthropology of Archaeological Populations from Northeast Asia (PDF). Dankook: Oriental Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-29. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- Vovin, Alexander (2000). "Did the Xiong-nu speak a Yeniseian language?". Central Asiatic Journal. 44 (1): 87–104. JSTOR 41928223.

- Vovin, Alexander (2003). Did the Xiongnu speak a Yeniseian language? Part 2: Vocabulary. Altaica Budapestinensia MMII.

- Vovin, Alexander; Edward Vajda; Étienne de la Vaissière (2016). Who were the *Kjet (羯) and what language did they speak?. Journal Asiatique.

- Vovin, Alexander (2015). ONCE AGAIN ON THE ETYMOLOGY OF THE TITLE qaγan. Cracovie: Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- A. Wink (2002). Al-Hind: making of the Indo-Islamic World. Brill. ISBN 0-391-04174-6.

- Xumeng, Sun (14 September 2020). Identifying the Huns and the Xiongnu (or Not): Multi-Faceted Implications and Difficulties (PDF). PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository (Thesis). Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- Ying-Shih Yü (1990). The Hsiung-Nu. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.